The clearest way to think about an AI-driven productivity shock is as a surplus engine whose benefits can either diffuse through wages, prices, and public goods—or pool in a few balance sheets. Because diffusion is not automatic, the next two decades will be defined less by the ingenuity of the models than by the ingenuity of our institutions. Probabilities help cut through the fog. What follows is a set of likelihoods for the dominant responses societies may adopt as cognitive automation compresses traditional employment. These figures are global, medium-term estimates for the 10–20 year horizon, and they describe which response is likely to become meaningfully present at national scale, not a fleeting pilot program or a line in a manifesto. They overlap by design: multiple responses will coexist, and probabilities indicate the chance that each becomes a mainstream feature of policy or the labor market in a significant share of countries.

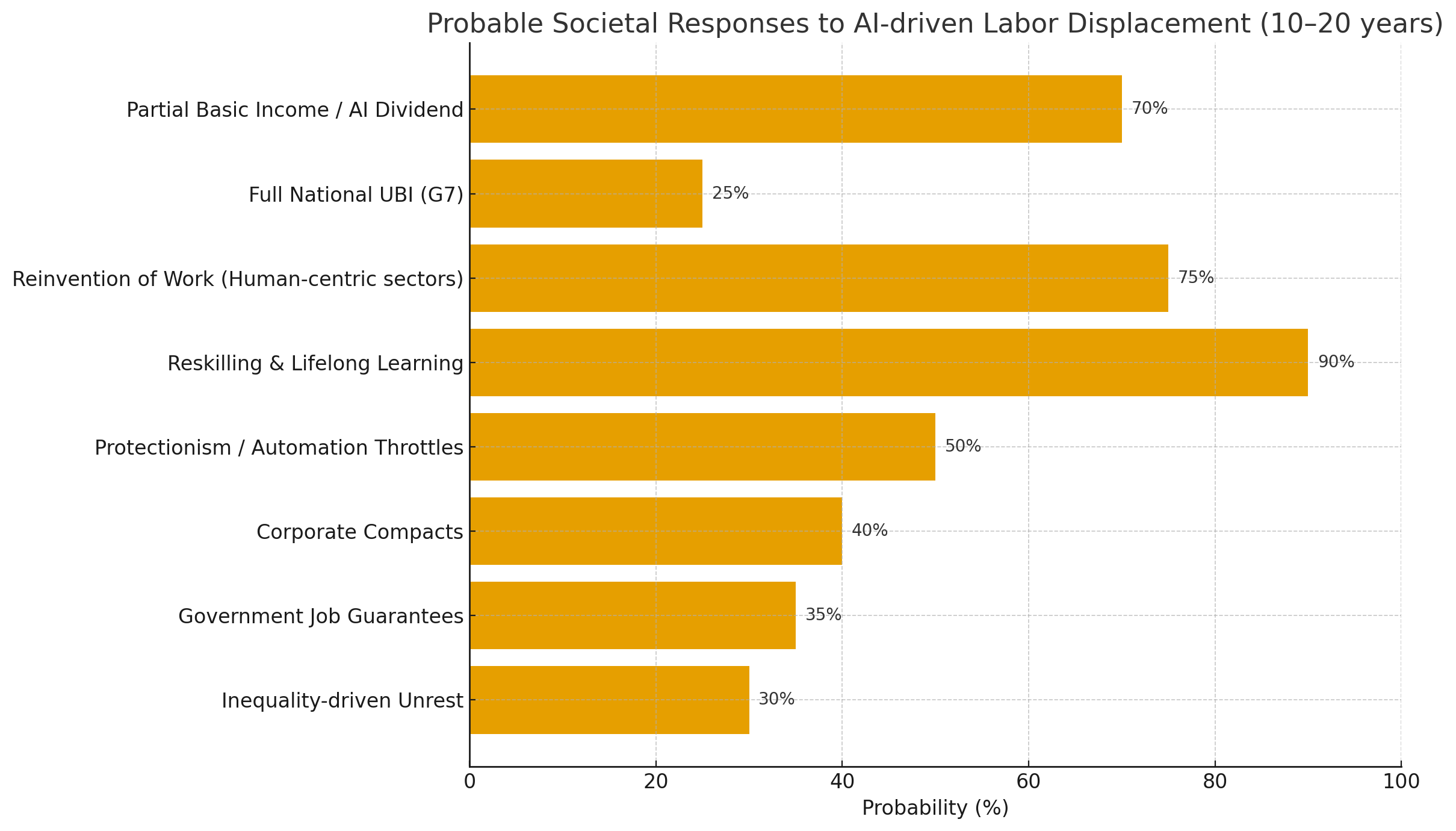

The first and most discussed response—broad redistribution via cash transfers—has a split personality. It is highly probable that “UBI-lite” instruments spread widely: wage top-ups, negative income tax designs, child and elder allowances, and permanent dividend-style stipends tied to automated productivity or sovereign wealth funds. There is roughly a 65–75% chance that by the late 2030s at least a third of advanced economies will run some combination of permanent cash transfers and refundable tax credits that cover a meaningful portion of household basics each month. By contrast, the probability that a full, unconditional national UBI becomes policy in at least one G7 country within twenty years is closer to 20–30%, with a 10–15% chance that two or more adopt it. The binding constraints are fiscal capacity, political appetite for broad-based taxation of capital and high earners, and public attitudes about reciprocity. Where resource revenues, sovereign wealth, or concentrated AI rents exist, the odds rise; where debt loads and political polarization dominate, the odds fall.

Reinvention of work—expansion of sectors where human presence, trust, taste, and touch matter more than throughput—looks less like a moonshot and more like a slow, sturdy tide. There is a 70–80% chance that care, education, mental health, hospitality, design, and experiential culture absorb at least 10–15% of workers displaced or compressed by AI in advanced economies, supported by lighter regulation, micro-enterprise platforms, and AI tools that amplify single-person businesses. The probability that these sectors absorb 25% or more is around 30–40%, contingent on two levers: whether governments use procurement and vouchers to stimulate demand for human-delivered services, and whether cities zone and tax to make small, human-scaled enterprises viable. This pathway does not restore the old factory-and-office equilibrium; it builds a parallel economy where authenticity is scarce and therefore valued.

Education and reskilling are the certain bet. Not because retraining alone “solves” displacement, but because every political coalition can support it, and because AI itself makes learning faster and cheaper. There is an 85–90% chance that most OECD countries institutionalize lifelong learning accounts, portable training credits, and public AI tutors woven into schools, job centers, and community colleges. A more specific claim carries slightly lower odds: a 50–60% chance that every citizen in at least a dozen countries will have a government-sponsored AI copilot for education and employment services, integrated with credentialing and job-matching systems. The effect will be uneven: reskilling works best when paired with wage insurance, portable benefits, and occupational licensing reform, without which training morphs into credential churn.

Protectionism and automation throttles will appear as pressure valves rather than permanent dams. Expect a 45–55% probability that multiple governments adopt targeted slowdowns—local content rules for public procurement, “human-in-the-loop” mandates for critical services, taxes or fees on fully automated customer support, or hiring floors in publicly funded projects. The chance that broad “robot taxes” become a durable revenue pillar is lower, around 15–25%, because measurement is messy and the risk of offshoring is real. Still, time-buying measures are politically attractive when unemployment rises rapidly or when specific regions—port cities, legacy manufacturing belts, call-center hubs—face concentrated shocks. Their staying power will depend on whether they are paired with a clear glide path to productivity-compatible, worker-centric models.

Corporate-led transition compacts—where large firms pledge to recycle AI gains into employee dividends, guaranteed upskilling time, or job-sharing—are more than public relations but less than a social contract. There is a 35–45% probability that such compacts become commonplace among the largest global employers, particularly those with strong brands or union partnerships, and a 10–15% chance of sector-wide “automation funds” financed by industry levies, analogous to extended producer responsibility in environmental policy. This path becomes likelier as talent scarcity persists in some domains even while others shrink, making retention and morale economically rational. The limiting factor is free-riding: unless participation is normalized by regulation, procurement rules, or investor pressure, the most extractive competitors will undercut the pact.

Government employment guarantees and mission-scale public works have better odds than many assume, especially in places with aging infrastructure and climate imperatives. There is a 30–40% probability that several middle- and high-income countries pilot or adopt multi-year, opt-in job guarantees oriented to eldercare, disability support, environmental remediation, and resilience projects. Execution risk is the hurdle—project design, supervision, and local capacity—but AI itself can mitigate that by improving matching, training, and oversight. Where debt constraints bite, guarantees will appear at municipal or regional scale first, underwritten by national transfers.

The tail-risk scenario—high inequality equilibria coupled with chronic unrest—cannot be waved away. If productivity gains are privatized and wages do not track efficiency, the probability that at least five mid-to-large economies experience multi-year political instability linked directly to job displacement is around 25–35%. There is a 10–15% chance that one or more such crises induce illiberal controls on information systems and labor mobility in the name of “stability,” choices that would sacrifice long-run innovation for short-term calm. The triggers to watch are a falling labor share of income alongside rising essential-goods inflation, automation surges in electoral swing regions, and fiscal austerity that erodes safety nets precisely when they are most needed.

Regional variation will be stark. The United States has a 60–70% chance of adopting a patchwork equilibrium—state-level earned-income top-ups, federal child and elder credits, large-scale reskilling, and corporate compacts in tech-heavy sectors—while a full national UBI remains a 20–25% proposition without a dedicated revenue source. The European Union collectively shows a 70–80% probability of “UBI-lite plus services,” with strong worker protections, universal benefits, and human-in-the-loop requirements in critical sectors; a few member states, particularly in the Nordics, could reach 30–40% odds for a true UBI funded by wealth and carbon/AI rents. China has a 50–60% chance of prioritizing state-directed employment programs, rapid reskilling, and automation mandates in strategic sectors, with cash transfers expanding but remaining targeted rather than universal. India’s trajectory leans 60–70% toward skills, digital identification–enabled transfers, and large public works, with urban employment guarantees gaining plausibility as cities swell. Resource-rich Gulf states and countries with sizable sovereign funds have a 40–50% chance of establishing permanent dividend-like transfers tied to automated productivity, while many emerging markets face a 30–40% risk of inequality-driven unrest unless paired with aggressive investment in education, infrastructure, and informal-to-formal transitions.

Two kinds of signposts will shift these odds in real time. Productivity and distribution metrics are the first: if AI raises total factor productivity by more than one percentage point annually for several years while the labor share of income falls, the probability weight moves toward redistribution and unrest simultaneously; if labor share holds steady because augmented workers capture value through bargaining, the weight moves toward reinvention and compacts. Institutional throughput is the second: successful passage of tax modernization, portable benefits, zoning reform for small enterprises, and procurement rules that price “human quality” will raise the likelihood that human-centric sectors expand enough to matter. Watch also for adoption of public AI copilots in schools and job centers, the speed of credential modernization, and the share of public and private capex dedicated to care and resilience.

What emerges from these probabilities is less a single recipe than a portfolio logic. The most likely steady state in advanced economies by the late 2030s is a mixed regime—high chance that partial basic income and refundable credits blunt income shocks; very high chance that reskilling is continuous and AI-assisted; strong chance that human-centric sectors expand significantly; meaningful but targeted use of automation throttles; and a nontrivial risk band of political instability where diffusion fails. The central task for policymakers and firms is to bend the distribution—of income, opportunity, and dignity—so that abundance does not curdle into exclusion. If they succeed, the probabilities that today look like hedges will compound into a new normal in which people work less for subsistence and more for meaning, without being coerced into a binary choice between machine efficiency and human worth.